Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most by Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, Sheila Heen of the Harvard Negotiation Project

Difficult Conversations

I have tried to keep the notes as neat as possible. You can find another great summary here –

http://www.fscanada.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Difficult-Conversations-Summary.pdf

– 3 Conversation

1. The “What Happened?” Conversation. Most difficult conversations involve disagreement about what has happened or what should happen. Who said what and who did what? Who’s right, who meant what, and who’s to blame?

2. The Feelings Conversation. Are my feelings valid? Appropriate? Should I acknowledge or deny them, put them on the table or check them at the door? What do I do about the other person’s feelings? What if they are angry or hurt? These feelings are not addressed directly in the conversation, but they leak in anyway.

3. The Identity Conversation. This is the conversation we each have with ourselves about what this situation means to us. We conduct an internal debate over whether this means we are competent or incompetent, a good person or bad, worthy of love or unlovable. What impact might it have on our self-image and self-esteem, our future and our well-being? Our answers to these questions determine in large part whether we feel “balanced” during the conversation, or whether we feel off-center and anxious.

– 3 fronts — Truth, Intentions, Blame

1. The Truth Assumption. As we argue vociferously for our view, we often fail to question one crucial assumption upon which our whole stance in the conversation is built: I am right, you are wrong. This simple assumption causes endless grief. There’s only one hitch: I am not right. They are not about what is true, they are about what is important. (Paras note: Something I say about relationships. Either one person wins/is right or the relationship wins/is right)

2. The Intention Invention. Did you yell at me to hurt my feelings or merely to emphasize your point? What I think about your intentions will affect how I think about you and, ultimately, how our conversation goes. We assume we know the intentions of others when we don’t. Worse still, when we are unsure about someone’s intentions, we too often decide they are bad. Sometimes people act with mixed intentions. Sometimes they act with no intention, or at least none related to us. And sometimes they act on good intentions that nonetheless hurt us.

3. The Blame Frame. Most difficult conversations focus significant attention on who’s to blame for the mess we’re in. We don’t care where the ball lands, as long as it doesn’t land on us. But talking about fault is similar to talking about truth—it produces disagreement, denial, and little learning. It evokes fears of punishment and insists on an either/or answer. Nobody wants to be blamed, especially unfairly, so our energy goes into defending ourselves. Talking about blame distracts us from exploring why things went wrong and how we might correct them going forward. Focusing instead on understanding the contribution system allows us to learn about the real causes of the problem, and to work on correcting them. The distinction between blame and contribution may seem subtle. But it is a distinction worth working to understand, because it will make a significant difference in your ability to handle difficult conversations.

– Why We Argue, and Why It Doesn’t Help. We think they are the problem. They think we are the problem. We each make sense in our story of what happened. Arguing blocks us from exploring each other’s stories. Arguing without understanding is unpersuasive.

– Move from Certainty to Curiosity. Curiosity: the way into their story. Embrace both stories: adopt the “and stance”. They can feel one thing and you can feel something totally opposite. Exceptions are I really am right (caught daughter smoking) and giving bad news (firing/breaking up).

– Disentangle Impact and Intent. Separating impact from intentions requires us to be aware of the automatic leap from “I was hurt” to “You intended to hurt me.” You can make this distinction by asking yourself three questions: 1. Actions: “What did the other person actually say or do?” 2. Impact: “What was the impact of this on me?” 3. Assumption: “Based on this impact, what assumption am I making about what the other person intended?” Share the Impact on You; Inquire About Their Intentions.

– Listen for Feelings, and Reflect on Your Intentions. When we find ourselves being accused of bad intentions — we have a strong tendency to want to defend ourselves: “That is not what I intended.” We are defending our intentions and our character. However, as we’ve seen, starting here leads to trouble.

– Listen Past the Accusation for the Feelings. Accusation about our bad intentions is always made up of two separate ideas: (1) we had bad intentions and (2) the other person was frustrated, hurt, or embarrassed. Don’t pretend they aren’t saying the first. You’ll want to respond to it. But neither should you ignore the second. And if you start by listening and acknowledging the feelings, and then return to the question of intentions, it will make your conversation significantly easier and more constructive.

– Be Open to Reflecting on the Complexity of Your Intentions. When it comes time to consider your intentions, try to avoid the tendency to say, “My intentions were pure.” We usually think that about ourselves, and sometimes it’s true. But often, as we’ve seen, intentions are more complex.

– Blame Is About Judging, and Looks Backward. Contribution Is About Understanding, and Looks Forward. Contribution is joint and interactive.

– Three Misconceptions About Contribution.

1: I should focus only on my contribution.

2: putting aside blame means putting aside my feelings.

3: exploring contribution means, “blaming the victim”.

– Four Hard-to-Spot Contributions.

1. Avoiding until now.

2. Being unapproachable.

3. Intersections.

4. Problematic role assumptions.

– Two Tools for Spotting Contribution. Role reversal. The observer’s insight.

– Map the Contribution System. What are they contributing? What am I contributing? List each person’s contribution. My contributions. His contributions. Who else is involved? Take responsibility for your contribution early. Help them understand their contribution. Make your observations and reasoning explicit. Clarify what you would have them do differently.

– Don’t Vent: Describe Feelings Carefully.

1. Frame feelings back into the problem.

2. Express the full spectrum of your feelings.

3. Don’t evaluate — just share. Express your feelings without judging, attributing, or blaming. Don’t monopolize: both sides can have strong feelings at the same time. An easy reminder: say “I feel . . . .”

– The Importance of Acknowledgment. What does it mean to acknowledge someone’s feelings? It means letting the other person know that what they have said has made an impression on you, that their feelings matter to you, and that you are working to understand them. “Wow,” you might say, “I never knew you felt that way,” or, “I kind of assumed you were feeling that, and I’m glad you felt comfortable enough with me to share it,” or, “It sounds like this is really important to you.” Let them know that you think understanding their perspective is important, and that you are trying to do so: “Before I give you a sense of what’s going on with me, tell me more about your feeling that I talk down to you.” Sometimes feelings are all that matter.

– Three Core Identities. Am I competent? Am I a good person? Am I worthy of love?

– Vulnerable Identities: the all-or-nothing syndrome. Denial. Exaggeration. We let their feedback define who we are.

– Ground Your Identity.

1: become aware of your identity issues.

2: complexify your identity (adopt the And Stance).

– Three Things to Accept About Yourself.

1. You will make mistakes.

2. Your intentions are complex.

3. You have contributed to the problem.

– Learn to Regain Your Balance. Let go of trying to control their reaction. Prepare for their response. Imagine that it’s three months or ten years from now. Take a break.

-Three Kinds of Conversations That Don’t Make Sense.

1: is the real conflict inside you?

2: is there a better way to address the issue than talking about it?

3: do you have purposes that make sense?

– Remember, You Can’t Change Other People. Don’t focus on short-term relief at long-term cost. Don’t hit-and-run. Letting go. Adopt some liberating assumptions. It’s not my responsibility to make things better; it’s my responsibility to do my best. They have limitations too. This conflict is not who I am. Letting go doesn’t mean I no longer care. Create a learning conversation.

– If You Raise It: Three Purposes That Work.

1. Learning their story.

2. Expressing your views and feelings.

3. Problem-solving together.

– Why Our Typical Openings Don’t Help. We begin inside our own story. We trigger their identity conversation from the start.

– Getting Started.

1: Begin from the Third Story. For example, in the battle between bicycles and cars for the streets of the city, the third story would be the one told by city planners, who can understand each side’s concerns and see why each group is frustrated with the other. When tensions arise in a marriage, the third story might be the one offered by a marriage counselor. In a dispute between friends, the third story may be the perspective of a mutual friend who sees each side as having valid concerns that need to be addressed. Think like a mediator. Not right or wrong, not better or worse – just different. If they start the conversation, you can still step to the third story.

2: Extend an Invitation. Describe your purposes. Invite, don’t impose. Make them your partner in figuring it out. Be persistent.

– “I Wonder If It Would Make Sense . . . ?” Revisiting conversations gone wrong. Talk about how to talk about it. A map for going forward: third story, their story, your story.

– What to Talk About: The Three Conversations (What Happened? Feeling. Identity). Explore where each story comes from. Share the impact on you. Take responsibility for your contribution. Describe feelings. Reflect on the identity issues. How to talk about it: listening, expression, and problem-solving.

– Listening to Them Helps Them Listen to You. The stance of curiosity: how to listen from the inside out. Forget the words, focus on authenticity. The commentator in your head: become more aware of your internal voice. Don’t turn it off, turn it up. Managing your internal voice. Negotiate your way to curiosity. Don’t listen: talk.

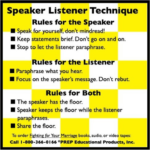

– Three Skills: 1: Inquiry, 2: Paraphrasing, and 3: Acknowledgment.

1: Inquire to Learn – don’t make statements disguised as questions. Don’t use questions to cross-examine. Ask open-ended questions. Ask for more concrete information. Create a learning conversation. Examples – can you say a little more about how you see things? What information might you have that I don’t? How do you see it differently? What impact have my actions had on you? Can you say a little more about why you think this is my fault? Were you reacting to something I did? How are you feeling about all of this? Say more about why this is important to you? What would it mean to you if that happened? Make it safe for them not to answer.

2: Paraphrase for Clarity – check your understanding. Show that you’ve heard. Create a learning conversation.

3: Acknowledge Their Feelings (Paras note: big one for me) – answer the invisible questions. How to acknowledge. Order matters: acknowledge before problem-solving. Acknowledging is not agreeing.

A final thought: empathy is a journey, not a destination

– Failure to Express Yourself Keeps You Out of the Relationship. Feel entitled, feel encouraged, but don’t feel obligated. Start with what matters most. Say what you mean: don’t make them guess. Don’t rely on subtext. Avoid easing in. Don’t make your story simplistic: use the “me-me” and.

Amazon #ads

Telling Your Story with Clarity: Three Guidelines.

1. Don’t Present Your Conclusions as The Truth.

2. Share Where Your Conclusions Come From.

3. Don’t Exaggerate with “Always” and “Never”.

“Always” and “never” do a pretty good job of conveying frustration, but they have two serious drawbacks. First, it is seldom strictly accurate that someone criticizes every time, or that they haven’t at some point said something positive. Using such words invites an argument over the question of frequency: “That’s not true. I said several nice things to you last year when you won the interoffice new idea competition”—a response that will most likely increase your exasperation.

“Always” and “never” also make it harder — rather than easier — for the other person to consider changing their behavior. In fact, “always” and “never” suggest that change will be difficult or impossible. The implicit message is, “What is wrong with you such that you are driven to criticize my clothes?” or even “You are obviously incapable of acting like a normal person.”

A better approach is to proceed as if (however hard it may be to believe) the other person is simply unaware of the impact of their actions on you, and, being a good person, would certainly wish to change their behavior once they became aware of it. You could say something like: “When you tell me my suit reminds you of wrinkled old curtains, I feel hurt. Criticizing my clothes feels like an attack on my judgment and makes me feel incompetent.” If you can also suggest what you would wish to hear instead, so much the better: “I wish I could feel more often like you believed in me. It would really feel great to hear even something as simple as, ‘I think that color looks good on you.’ Anything, as long as it was positive.”

The key is to communicate your feelings in a way that invites and encourages the recipient to consider new ways of behaving, rather than suggesting they’re a schmuck and it’s too bad there’s nothing they can do about it.

– Give Them Room to Change. Help them understand you. Ask them to paraphrase back. Ask how they see it differently — and why.

– You can reframe anything. The ‘you-me’ and (I can try to understand you and you can try to understand me). It’s always the right time to listen. Be persistent about listening. It takes two to agree. Gather information and test your perceptions. Say what is still missing. Say what would persuade you. Ask what (if anything) would persuade them. Ask their advice. Invent options. Ask what standards should apply. The principle of mutual caretaking. If you still can’t agree, consider your alternatives.

– Putting It All Together. (See below checklist for more details). 1: prepare by walking through the three conversations. 2: check your purposes and decide whether to raise it. 3: start from the third story. 4: explore their story and yours. 5: problem-solving.

– Expression: Speak for Yourself with Clarity and Power. Orators need not apply. You’re entitled (yes, you). Failure to express yourself keeps you out of the relationship. Feel entitled, feel encouraged, but don’t feel obligated. Start with what matters most. Say what you mean: don’t make them guess. Don’t rely on subtext. Avoid easing in.

– Don’t Make Your Story Simplistic: Use the “Me-Me” And. “This memo shows incredible creativity, and at the same time is so badly organized that it makes me crazy.” In your attempt to be clear, you say, “Your memo is so badly organized it makes me crazy,” or worse, “Your memo makes me crazy.”

– Problem-Solving: Take the Lead. Reframe, reframe, reframe! You can reframe anything. The “you-me” and (“I can listen and understand what you have to say, and you can listen and understand what I have to say.”). It’s always the right time to listen. Name the dynamic: make the trouble explicit. Now what? Begin to problem-solve. It takes two to agree.

– Gather Information and Test Your Perceptions. Propose crafting a test. Say what is still missing. Say what would persuade you. Ask what (if anything) would persuade them. Ask their advice. Invent options. Ask what standards should apply. The principle of mutual caretaking. If you still can’t agree, consider your alternatives.

– Difficult conversation checklist

Step 1: Prepare by Walking Through the Three Conversations

– Sort out What Happened. Where does your story come from (information, past experiences, rules)? Theirs? What impact has this situation had on you? What might their intentions have been?

What have you each contributed to the problem?

– Understand Emotions.

Explore your emotional footprint, and the bundle of emotions you experience.

– Ground Your Identity. What’s at stake for you about you? What do you need to accept to be better grounded?

Step 2: Check Your Purposes and Decide Whether to Raise the Issue

– Purposes: What do you hope to accomplish by having this conversation? Shift your stance to support learning, sharing, and problem-solving.

– Deciding: Is this the best way to address the issue and achieve your purposes? Is the issue really embedded in your Identity Conversation? Can you affect the problem by changing your contributions? If you don’t raise it, what can you do to help yourself let go?

Step 3: Start from the Third Story

– Describe the problem as the difference between your stories. Include both viewpoints as a legitimate part of the discussion.

– Share your purposes.

– Invite them to join you as a partner in sorting out the situation together.

Step 4: Explore Their Story and Yours

– Listen to understand their perspective on what happened. Ask questions. Acknowledge the feelings behind the arguments and accusations. Paraphrase to see if you’ve got it. Try to unravel how the two of you got to this place.

– Share your own viewpoint, your past experiences, intentions, feelings.

– Reframe, reframe, reframe to keep on track. From truth to perceptions, blame to

contribution, accusations to feelings, and so on.

Step 5: Problem-Solving

– Invent options that meet each side’s most important concerns and interests.

– Look to standards for what should happen. Keep in mind the standard of mutual caretaking; relationships that always go one way rarely last.

– Talk about how to keep communication open as you go forward.

Contents:

Foreword by Roger Fisher

Acknowledgments

Introduction

The Problem

1 Sort Out the Three Conversations

Shift to a Learning Stance – The “What Happened?” Conversation

2 Stop Arguing About Who’s Right: Explore Each Other’s Stories

3 Don’t Assume They Meant It: Disentangle Intent from Impact

4 Abandon Blame: Map the Contribution System

– The Feelings Conversation

5 Have Your Feelings (Or They Will Have You)

– The Identity Conversation

6 Ground Your Identity: Ask Yourself What’s at Stake

– Create a Learning Conversation

7 What’s Your Purpose? When to Raise It and When to Let Go

8 Getting Started: Begin from the Third Story

9 Learning: Listen from the Inside Out

10 Expression: Speak for Yourself with Clarity and Power

11 Problem-Solving: Take the Lead

12 Putting It All Together

A Road Map to Difficult Conversations

A Note on Some Relevant Organizations

Bonus: Difficult Conversations (2016) by Michael Grinder & Associates

Amazon #ads