The Drama of the Gifted Child – The Search for the True Self by Alice Miller

Summary by Yetieater:

Summary:* By “mother/father” I here understand the person closest to the child during the first years of life. This need not be the biological mother/father nor even a woman. In the course of the past twenty years, quite often the fathers have assumed this mothering function.

– Thanks to Gabor Mate for the recommendation. (See link for more from him)

– Lots of examples and case studies.

– A mother/father who, as a child, was herself not taken seriously by her mother/father as the person she really was will crave this respect from her child as a substitute; and she will try to get it by training him to give it to her. The tragic fate that is the result of such training and such “respect” is described in this book.

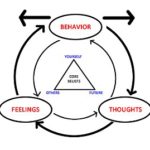

– It is inconceivable to love others (not merely to need them), if one cannot love oneself as one really is. And how could a person do that if, from the very beginning, he has had no chance to experience his true feelings and to learn to know himself?

Amazon #ads

– The child has a primary need to be regarded and respected as the person he really is at any given time, and as the centre — the central actor — in his own activity. In contra-distinction to drive wishes, we are speaking here of a need that is narcissistic, but nevertheless legitimate, and whose fulfilment is essential for the development of a healthy self-esteem.

– Parents who did not experience this climate as children are themselves narcissistically deprived; throughout their lives they are looking for what their own parents could not give them —the presence of a person who is completely aware of them and takes them seriously, who admires and follows them.

– They have all developed the art of not experiencing feelings, for a child can only experience his feelings when there is somebody there who accepts him fully, understands and supports him. If that is missing, if the child must risk losing the mother/father’s love, then he cannot experience these feelings secretly “just for himself” but fails to experience them at all. But nevertheless . .. something remains.

– Accommodation to parental needs often (but not always) leads to the “as-if personality” (Winnicott has described it as the “false self”). This person develops in such a way that he reveals only what is expected of him, and fuses so completely with what he reveals that—until he comes to analysis—one could scarcely have guessed how much more there is to him, behind this “masked view of himself” (Habermas, 1970). He cannot develop and differentiate his “true self,” because he is unable to live it. It remains in a “state of noncommunication,” as Winnicott has expressed it. Understandably, these patients complain of a sense of emptiness, futility, or homelessness, for the emptiness is real. A process of emptying, impoverishment, and partial killing of his potential actually took place when all that was alive and spontaneous in him was cut off. In childhood these people have often had dreams in which they experienced themselves as partly dead. (Examples of dreams and case studies).

– The difficulties inherent in experiencing and developing one’s own emotions lead to bond permanence, which prevents individuation, in which both parties have an interest. The parents have found in their child’s “false self the confirmation they were looking for, a substitute for their own missing structures; the child, who has been unable to build up his own structures, is first consciously and then unconsciously (through the introject) dependent on his parents. He cannot rely on his own emotions, has not come to experience them through trial and error, has no sense of his own real needs, and is alienated from himself to the highest degree. Under these circumstances he cannot separate from his parents, and even as an adult he is still dependent on affirmation from his partner, from groups, or especially from his own children. The heirs of the parents are the introjects, from whom the “true self” must remain concealed, and so loneliness in the parental home is later followed by isolation within the self. Narcissistic cathexis of her child by the mother/father does not exclude emotional devotion. On the contrary, she loves the child, as her self-object, excessively, though not in the manner that he needs, and always on the condition that he presents his “false self.” This is no obstacle to the development of intellectual abilities, but it is one to the unfolding of an authentic emotional life.

– In analysis, the small and lonely child that is hidden behind his achievements wakes up and asks: “What would have happened if I had appeared before you, bad, ugly, angry, jealous, lazy, dirty, smelly? Where would your love have been then? And I was all these things as well. Does this mean that it was not really me whom you loved, but only what I pretended to be? The well-behaved, reliable, empathic, understanding, and convenient child, who in fact was never a child at all? What became of my childhood? Have I not been cheated out of it? I can never return to it. I can never make up for it. From the beginning I have been a little adult. My abilities-were they simply misused?” These questions are accompanied by much grief and pain, but the result always is a new authority that is being established in the analysand (like a heritage of the mother/father who never existed) – a new empathy with his own fate, born out of mourning.

– Once these grandiose fantasies (often accompanied by obsessional or perverse phenomena) have been experienced and understood as the alienated form of these real and legitimate needs, the split can be overcome and integration can follow. What is the chronological course?

1 – In the majority of cases, it is not difficult to point out to the patient early in his analysis the way he has dealt with his feelings and needs, and that this was a question of survival for him. It is a great relief to him that things he was accustomed to choke off can be recognised and taken seriously. Gradually, the patient himself realises how he is forced to look for distraction when he is moved, upset, or sad. There are still many situations where he sees himself as other people see him, constantly asking himself what impression he is making, and how he ought to be reacting or what feelings he ought to have. But on the whole he feels much freer in this initial period and, thanks to the analyst as his auxiliary ego, he can be more aware of himself when his immediate feelings are experienced within the session and taken seriously. He is very grateful for this possibility, too.

2 – In addition to this first function, which will continue for a long time, the analyst must take on a second as soon as the transference neurosis has developed: that of being the transference figure. Feelings out of various periods of childhood come to the surface then. This is the most difficult stage in analysis, when there is most acting out. The patient begins to be articulate and breaks with his former compliant attitudes, but because of his early experience he cannot believe this is possible without mortal danger. The compulsion to repeat leads him to provoke situations where his fear of object loss, rejection, and isolation has a basis in present reality, situations into which he drags the analyst with him (as a rejecting or demanding mother/father, for example), so that afterward he can enjoy the relief of having taken the risk and been true to himself. This can begin quite harmlessly. The patient is surprised by feelings that he would rather not have recognised, but now it is too late, awareness of his own impulses has already been aroused and there is no going back. Now the analysand must (and also is allowed to!) experience himself in a way he had never before thought possible. Now he is suddenly furious that his analyst again is going on vacation. Or he is annoyed to see other people waiting outside the consulting room. What can this be? Surely not jealousy. That is an emotion he does not recognise! and yet. . . . “What are they doing here? Do others besides me come here?” At first it is mortifying to see that he is not only good, understanding, tolerant, controlled and, above all, adult, for this was always the basis of his self-respect. But another, weightier mortification is added to the first when this analysand discovers the introjects within himself, and that he has been their prisoner. The patient is horrified when he realises that he is capable of screaming with rage in the same way that he so hated in his father, or that, only yesterday, he has checked and controlled his child, “practically,” he says, “in my mother/father’s clothes!” This revival of the introjects, and learning to come to terms with them forms the major part of the analysis. What cannot be recalled is unconsciously reenacted and thus indirectly discovered. The more he is able to admit and experience these early feelings, the stronger and more coherent the patient will feel. This in turn enables him to expose himself to emotions that well up out of his earliest childhood and to experience the helplessness and ambivalence of that period.

3 – The phase of separation begins when the analysand has reliably acquired the ability to mourn and can face feelings from his childhood, without the constant need for the analyst.

– But the child cannot experience this contradiction consciously; he simply accepts everything and, at the most, develops symptoms. Then, in analysis, the feelings emerge: feelings of terror, of despair and rebellion, of mistrust but also of compassion and reconciliation.

“You can drive the devil out of your garden but you will find him again in the garden of your son.”

– What is described as depression and experienced as emptiness, futility, fear of impoverishment, and loneliness can often be recognised as the tragedy of the loss of the self, or alienation from the self, from which many suffer in our generation and society.

– Every child has a legitimate narcissistic need to be noticed, understood, taken seriously, and respected by his mother/father. In the first weeks and months of life he needs to have the mother/father at his disposal, must be able to use her and to be mirrored by her.

– Various investigations have shown the incredible ability that a healthy child displays in making use of the smallest affective “nourishment” (stimulation) to be found in his surroundings.

– The mother/father, who apparently functioned well, was herself basically still a child in her relationship to her own child. The daughter, on the other hand, took over the understanding and caring role until she discovered, with her own children, the demanding child within herself who seemed compelled to press others into her service.

– We find various mixtures and nuances of narcissistic disturbances. Grandiosity and depression. Behind manifest grandiosity, there constantly lurks depression, and behind a depressive mood there often hide unconscious (or conscious but split off) fantasies of grandiosity. In fact, grandiosity is the defence against depression, and depression is the defence against the deep pain over the loss of the self.

Grandiosity. The person who is “grandiose” is admired everywhere and needs this admiration; indeed, he cannot live without it. He must excel brilliantly in everything he undertakes, which he surely is capable of doing (otherwise he just does not attempt it). He, too, admires himself—for his qualities: his beauty, cleverness, talents—and for his success and achievements. Woe betide if one of these fails him, for then the catastrophe of a severe depression is imminent. It is usually considered normal that sick or aged people who have suffered the loss of much of their health and vitality, or, for example, women at the time of the menopause, should become depressive. There are, however, other personalities who can tolerate the loss of beauty, health, youth, or loved ones, and although they mourn them they do so without depression. In contrast, there are those with great gifts, often precisely the most gifted, who suffer from severe depression. One is free from depression when self-esteem is based on the authenticity of one’s own feelings and not on the possession of certain qualities.

The collapse of self-esteem in a “grandiose” person will show clearly how precariously that self-esteem had been hanging in the air—”hanging from a balloon,” a female patient once dreamed. That balloon flew up very high in a good wind but then suddenly got a hole and soon lay like a little rag on the ground.. .. For nothing genuine that could have given strength and support later on had even been developed.

The “grandiose” person’s partners (including sexual partners) are also narcissistically cathected. Others are there to admire him, and he himself is constantly occupied, body and soul, with gaining that admiration. This is how his torturing dependence shows itself. The childhood trauma is repeated: he is always the child whom his mother/father admires, but at the same time he senses that so long as it is his qualities that are being admired, he is not loved for the person he really is at any given time. In the parents’ feelings, dangerously close to pride in their child, shame is con- cealedlest he should fail to fulfil their expectations.

The grandiose person is never really free, first, because he is excessively dependent on admiration from the object, and second, because his self-respect is dependent on qualities, functions, and achievements that can suddenly fail.

Depression as the Reverse of Grandiosity. The so-called phallic, narcissistic men can experience their ageing in a similar way, even if a new love affair may seem to create the illusion of their youth for a time and in this way may introduce brief manic phases into the early stages of the depression caused by their ageing.

This combination of alternating phases of grandiosity and depression can be seen in many other people. They are the two sides of the medal that could be described as the “false self”.

Continuous performance of outstanding achievements may sometimes enable an individual to maintain the illusion of constant attention and availability of his self-object (whose absence, in his early childhood, he must now deny just as much as his own emotional reactions). Such a person is usually able to ward off threatening depression with increased displays of brilliance, thereby deceiving both himself and those around him. However, he quite often chooses a marriage partner who either already has strong depressive traits or at least, within their marriage, unconsciously takes over and enacts the depressive components of the grandiose partner. This means that the depression is outside. The grandiose one can look after his “poor” partner, protect him like a child, feel himself to be strong and indispensable, and thus gain another supporting pillar for the building of his own personality, which actually has no secure foundations and is dependent on the supporting pillars of success, achievement, “strength,” and, above all, of denying the emotional world of his childhood.

Finally, depression can be experienced as a constant and overt dejection that appears to be unrelated to grandiosity. However, the repressed or split-off fantasies of grandiosity of the depressive are easily discovered, for example, in his moral masochism. He has especially severe standards that apply only to himself. In other people he accepts without question thoughts and actions that, in himself, he would consider mean or bad when measured against his high ego ideal. Others are allowed to be “ordinary,” but that he can never be.

Although the outward picture of depression is quite the opposite of that of grandiosity and has a quality that expresses the tragedy of the loss of self to a great extent, they have the same roots in the narcissistic disturbance. Both are indications of an inner prison, because the grandiose and the depressive individuals are compelled to fulfil the introjected mother/father’s expectations: whereas the grandiose person is her successful child, the depressive sees himself as a failure.

They have many points in common:

– A “false self” that has led to the loss of the potential “true self”.

– A fragility of self-esteem that is based on the possibility of realising the “false self” because of lack of confidence in one’s own feelings and wishes.

– Perfectionism, a very high ego ideal.

– Denial of the rejected feelings (the missing of a shadow in the reflected image of Narcissus).

– A preponderance of narcissistic cathexis of objects.

– An enormous fear of loss of love and therefore a great readiness to conform.

– Envy of the healthy.

– Strong aggression that is split off and therefore not neutralised.

– Oversensitivity.

– A readiness to feel shame and guilt.

– Restlessness.

– What an unfair situation it is when a child is opposed by two big, strong adults, as by a wall; we call it “consistency in up-bringing” when we refuse to let the child complain about one parent to the other.

– Contempt for those who are smaller and weaker thus is the best defence against a breakthrough of one’s own feelings of helplessness: it is an expression of this split-off weakness. The strong person who knows that he, too, carries this weakness within himself, because he has experienced it, does not need to demonstrate his strength through such contempt.

– We find a similar example in the behaviour of addicts, in whom the object relationship has already been internalised. People who as children successfully repressed their intense feelings often try to regain—at least for a short time—their lost intensity of experience with the help of drugs or alcohol.

– If we want to avoid the unconscious seduction and discrimination against the child, we must first gain a conscious awareness of these dangers. Only if we become sensitive to the fine and subtle ways in which a child may suffer humiliation can we hope to develop the respect for him that a child needs from the very first day of his life onward, if he is to develop emotionally. There are various ways to reach this sensitivity. We may, for instance, observe children who are strangers to us and attempt to feel empathy for them in their situation—or we might try to develop empathy for our own fate. For us as analysts, there is also the possibility of following our analysand into his past—if we accept that his feelings will tell us a true story that so far no one else knows.

– Many people suffer all their lives from this oppressive feeling of guilt, the sense of not having lived up to their parents’ expectations. This feeling is stronger than any intellectual insight that it is not a child’s task or duty to satisfy his parent’s narcissistic needs. No argument can overcome these guilt feelings, for they have their beginnings in life’s earliest period, and from that they derive their intensity and obduracy.

– That probably greatest of narcissistic wounds—not to have been loved just as one truly was—cannot heal without the work of mourning. It can either be more or less successfully resisted and covered up (as in grandiosity and depression), or constantly torn open again in the compulsion to repeat.

– A person can have adapted completely to the demands of his surroundings and can have developed a false self, but in his perversion or his obsessional neurosis he still allows a portion of his true self to survive—in torment. And so the true self lives on, under the same conditions as the child once did with his disgusted mother/father, whom in the meantime he has introjected. In his perversion and obsessions he constantly reenacts the same drama: a horrified mother/father is necessary before drive-satisfaction is possible: orgasm (for instance, with a fetish) can only be achieved in a climate of self-contempt; criticism can only be expressed in (seemingly) absurd, unaccountable (frightening), obsessional fantasies.

– A person who suffers under his perversion bears within himself his mother/father’s rejection, and thus he flaunts his perversion, in order to get others to reject him, too, all the time—so re-externalising the rejecting mother/father. For this reason he feels compelled to do things that his circle and society disapprove of and despise. If society were suddenly to honour his form of perversion, he would have to change his compulsion, but it would not free him. What he needs is not permission to use one or another fetish, but the disgusted and horrified eyes. If he comes to analysis he will look for this in his analyst, too, and will have to use all possible means to provoke him to disgust, horror, and aversion. This provocation is of course a part of the transference, and from the incipient countertransference reactions one can surmise what happened at the beginning of this life.

– One can therefore hardly free a patient from the cruelty of his introjects by showing him how the absurdity, exploitation, and perversity of society causes our neuroses and perversions, however true this may be.

– Our patients are intelligent, they can tell about the absurdities of life. What they do not see, because they cannot see it, is the absurdities of their own mothers/fathers at the time when they still were tiny children. One cannot remember one’s parents’ attitudes then, because one was a part of them, but in analysis this early interaction can be recalled and parental constraints are thus more easily disclosed.

– The inner necessity to constantly build up new illusions and denials, in order to avoid the experience of our own reality, disappears once this reality has been faced and experienced. We then realise that all our lives we have feared and struggled to ward off something that really cannot happen any longer: it has already happened, happened at the very beginning of our lives while we were completely dependent.

– Many parents, even with the best intentions, cannot always understand their child, since they, too, have been stamped by their experience with their own parents and have grown up in a different generation. It is indeed a great deal when parents can respect their children’s feelings even when they cannot understand them.

– The patient was the more astonished when, toward the end of his analysis, he dreamed that he was suddenly sitting in this elevator in the tower again and was drawn upward as in a chair lift without feeling any fear. He enjoyed the ride, got out at the top and, strange to say, there was colourful life all about him. It was a plateau, and from it he had a view of the valleys. There was also a town up there, with a bazaar full of colourful wares; a school where children were practicing ballet and he could join in (this had been a childhood wish); and groups of people holding discussions with whom he sat and talked. He felt integrated into this society, just as he was. This dream impressed him deeply and made him happy.

– There are moments in every analysis when dammed-up demands, fears, criticism, or envy break through for the first time. With amazing regularity these impulses appear in a guise that the patient has never expected or that he might even have rejected and feared all his life. Before he can develop his own form of criticism he first adopts his father’s hated vocabulary or nagging manner. And the long repressed anxiety will surface in— of all things!—his mother/father’s irritating hypochondriacal fears. It is as if the “badness” in the parents that had caused a person the most suffering in his childhood and that he had always wanted to shun, has to be discovered within himself, so that reconciliation will become possible. Perhaps this also is part of the never-ending work of mourning that this personal stamp must be accepted as part of one’s own fate before one can become at least partially free.

– When the patient has truly emotionally worked through the history of his childhood and thus regained his sense of being alive—then the goal of the analysis has been reached. Afterward, it is up to the patient whether he will take a regular job or not; whether he wants to live alone or with a partner; etc – all that is his own decision. His life story, his experiences, and what he has learned from them will all play a role in how he will live. It is not the task of the analyst to “socialise” him, or “to bring him up” (for every form of bringing up denies his autonomy), nor to make “friendships possible for him”— all that is his own affair.

– When the patient, in the course of his analysis, has consciously repeatedly experienced (and not only learned from the analyst’s interpretations) how the whole process of his bringing-up did manipulate him in his childhood, and what desires for revenge this has left him with, then he will see through manipulation quicker than before and will himself have less need to manipulate others. Such a patient will be able to join groups without again becoming helplessly dependent or bound, for he has gone through the helplessness and dependency of his childhood in the transference.

– He will be in less danger of idealising people or systems if he has realised clearly enough how as a child he had taken every word uttered by mother/father or father for the deepest wisdom. He may experience, however, while listening to a lecture or reading a book, the same old childish fascination and admiration—but he will recognise at the same time the underlying emptiness or human tragedy that lurks behind these words and shudder at it. Such a person cannot be tricked with fascinating, incomprehensible words, since he has matured through his own experience.

– Finally, a person who has consciously worked through the whole tragedy of his own fate will recognise another’s suffering more clearly and quickly, though the other may still have to try to hide it. He will not be scornful of others’ feelings, whatever their nature, because he can take his own feelings seriously. He surely will not help to keep the vicious circle of contempt turning.

Contents:

– Vantage Point

– Preface

– Foreword

Chapter 1 – The Drama of the Gifted Child and the Psychoanalyst’s Narcissistic Disturbance

– The Poor Rich Child

– The Lost World of Feelings

– In Search of the True Self

– The Psychoanalyst’s Situation

– Concluding Remarks

Chapter 2 – Depression and Grandiosity as Related Forms of Narcissistic Disturbance

– The Vicissitudes of Narcissistic Needs

Health Narcissism

Narcissistic Disturbance

– The Legend of Narcissus

– Depressive Phases During Analysis

Signal Function

Denial of Self

The Accumulation of Strong, Hidden Feelings

The Struggle with the Introjects

– The Inner Prison and Analytic Work

– A Social Aspect of Depression

– Points of Contact with Some Theories of Depression

Chapter 3 – The Vicious Circle of Contempt

– Humiliation for the Child, Contempt for the Weak, and Where It Goes from There

Everyday Examples

– Introjected Contempt in the Mirror of Psychoanalysis

Damaged Self-articulation in the Compulsion to Repeat

Perpetuation of Contempt in Perversion and Obsessional Neurosis

‘Depravity’ in Herman Hesse’s Childhood World as an Example of Concrete ‘Evil’

Achieving Freedom from the Contemptuous Introjects

– Works Cited

– Index